Of Time and Rebellion

Talking to Jesus, Tupac, Socrates and our ancestors while camping with loons in the Adirondacks.

I was driving south out of the Adirondacks toward the Berkshires when it occurred to me the idea of days is an illusion. For years I’ve been convinced that our cities demote time from its proper standing as a mystery to a host of restrictions meant to accelerate economic growth. My rebellion against this abuse of time began as far back as kindergarten, when I was shaken out of sleep, plumped up on cinnamon toast, and shuttled off to Catholic school in a pair of blue rubber rain boots.

I can remember wailing as my mother departed. That first year of schooling wasn’t bad, even if the principal of the outfit—a squat, imposing nun—stuffed a bar of soap in my mouth after I gave her some lip for telling me to pick up spilled batteries off the floor. As I was already in the process of doing so, I said, “What the fuck does it look like I’m doing?”

This sort of commonsense retort was evidently beyond the pale. She dragged me by the ear down the hallway to the office and introduced me to a bar of Ivory. Too bad for her she was boiling warrior blood, so from that day forth I questioned every inanity I encountered as one institution after another did its best to brainwash me into believing it held the truth. Fat chance. I owe the old tyrant a bit of gratitude. She saved me from decades of blind faith.

It was the Babylonians who gave us the idea of cycles lasting seven days, a tradition of organizing time a mere four-thousand years old. How folks simply accept things as they are has long baffled me. The earliest evidence of human presence in North America goes back 23,000 years, something they failed to tell me in Catholic school, probably because the cognitive load of understanding the miracle of virgin conception was taxing enough to my young brain. Among my peers back then and even now, few bother to ask what those peeps 23,000 years ago thought of time.

Did they also carve up the lunar year into seven day cycles? Almost certainly, the answer is no. Tupac and Socrates, what would they think? Didn’t the brown-skinned brother Jesus extemporize on the Greek concept of kairos, time as opportune moments?

Didn’t he say, “ego eimi.”

“I am.” As in before the first son, he was. God was. The Creator was. Time was. What do we call someone who frees time from the normalized constraints of our culture?

Hippie, the old men sipping coffee at the gas station may say.

In my favorite drama, Arcadia, by playwright Tom Stoppard, characters from the past share the stage with characters from the present. The stage acts as a palimpsest for layers of time existing simultaneously. An amusing meditation on the universality of human longing, the drama is also a brilliant piece of literature incorporating the enigma of Chaos Theory and the unfortunate reality of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This intellectually weighty material is buried masterfully in the narrative arc of the story. It is one of those rare creations where you close quietly with your hands the thin pages and sit for a long time after thinking, holy hell how is it possible to be so good. Thinking that art is close to god.

Indigenous cultures view time as qualitative and relational rather than as quantitative and absolute, which aligns well with Italian physicist Carlo Rovelli’s argument that time emerges through relationships and interactions rather than existing independently. I’ve done my absolute best to live according to this perspective, but after so many years the fight in me has begun to diminish. There are only so many shifts you can show up late to work and tell your superiors that you are personally undermining the foundations of the Gregorian calendar.

“Gregory is fifteen minutes early every shift!”

“Go Gregory!”

Recently, Miss FPJ and I hiked into the backcountry for her first taste of summer camping. She grew up in Las Vegas, where they filmed The Jetsons, my all time childhood favorite because George Jetson’s work day consists of an hour a day, two days a week, which is even less work per week than the Internet Wizard Tim Ferriss recommends. George is my hero. Sorry Tim, but you talk too much, which is unlike ancient wizards.

We found ourselves on a remote pond a handful of miles from roads. Getting there required enduring Biblical levels of mosquitoes, but I’m glad we persevered because the trip turned out to be exactly what we needed. Like most modern Americans, we squander the bulk of our lives indentured to economic imperatives rather than to soul imperatives.

I have friends who prep all their meals on Sunday, like the week ahead means war. Efficiency is good practice, yes, but count me among the Ikarians who graze weeds like goats during seasons of lean growth. Optimization is largely accomplished by beating the feral out of life. I refuse to meal prep because the microwave traumatized me as a child when I cooked a bag of popcorn for thirty-three minutes while home alone. If you hit an extra number the whole village may go down in flames.

In America we are most of us addled by a collective frenzy. The pressures are immense. This does terrible injustice to the true nature of time, which as I stated before is qualitative rather than quantitative. If we are always rushing, then the quality is affected. Time becomes onerous, scarce, and dictatorial. Before we know it our lives warp according to the gravity of exigencies we find mundane and wholly unaligned with our basic needs as animals. Adult life in America is making plans with another adult for the following month only to see them ten years later. We are too busy.

On the pond, we pitched our tent in the shade of a hemlock tree. There were wild daisies poking up through the ground everywhere and a gentle breeze knocking the mosquitoes down. A rock ledge led to the water. It was perfect, about as summery a place as it gets for one’s first backcountry camping experience. We swam for hours as gradually the toxicity of the modern grind sloughed off.

With my phone powered down, I felt zero interest in everything but the phenomena around me: the wind, the clouds, the flowers, and Miss FPJ out there in the pond, floating like a lily flower under the sun. As a cancer patient, I’ve seen what’s coming, so I’m overly sensitive to the fact that the moment is not a prelude to the future. It is the future, and it is always slipping away. To see her swimming swelled my being with a sense of gratitude so capacious it felt as if the sky were raining seeded watermelons unbounded enough by mechanical laws to land softly as feathers.

When I was a child in the desert, this is how I imagined the lives of other kids. We didn’t go camping. We swam in water parks. There were no wild animals. I don't know why, but I have always longed for life on a farm. That’s what I imagined as a young girl. I drew pictures of horses. I wanted a dog, but my father is asthmatic. This is like my dream of summer. Is this real?

A dream came true. I didn’t have a yacht, but I had this: I could take her anywhere in the mountains and show her how to thrive. I could show her what mushrooms to eat, where to excrete, how to start a fire in the rain. I could show her the trees and tell her their names and guide her to submerged rocks far out in the pond that she could stand on, rocks slick with algae in whose underwater shadows swam native brook trout with vermiculite patterns on their skins. I could share what I knew, which was this place and all that it had taught me.

There were only basic tasks to do. We needed ready-made catholes for the morning. We needed birch bark for starting fires. We needed fire wood. I attended to these things, wandering through the adjacent forest in more than a mild state of awe. Out of the duff grew countless fungi. Lichens pulsed with green.

There were hundreds of salamanders on the march, more than I’d seen ever in other regions of the Adirondacks, so many of them we took to calling the place Manderville. It was work to not step on them. The woods hummed with an awareness I could fully sense but not reduce to language. The absence of automobiles and their horrible stench and the nervous system shattering noises they emit landed me in a place of calm.

Miss Front Porch Journal morphed into an otter. She swam further from shore than I was expecting her to. Dutch was there, and he was in full berserker mode, tearing at sticks, jumping off the ledge into the lake chasing after a loon who welcomed him, swimming back toward me, then toward Miss FJP, then toward the loon, then toward me. He wanted it all. No, he had it all. It was paradise for a lab.

Around dusk, I built myself a little fire beside the pond, then jumped naked into the cool water. Little in life can top this experience. After I toweled off, I stood beside the fire of beech logs while brushing my teeth. Above me, the loon we’d swam with all day was flying overhead in circles. Its wings made a squeaking sound as it passed ten feet above me. I wondered if it was leaving for another pond or a nearby lake. They were everywhere in this country. It is a land bejeweled with bodies of water.

I hoped it wasn’t leaving because of all the birds there is something about the loon that vitalizes me the way wolves and grizzly bears do. I’m a hunter, but even if it was legal to harvest loons, I never would. I would rather starve to death. This sounds extreme, but I’m not famous for being temperate.

The loon did not leave. It circled around and around and around as wisps of pink and lavender clouds scudded above the pond and a stiff breeze rose waves in its wake. You could say it was serene because it was, but words are poor substitutes for the magic of the earth in its becoming.

The shores of the pond were ringed by thickly forested green mountains. The loon swished above me. Five times he circled the pond, higher with each circle. Halfway through the sixth lap he pivoted and turned around in the other direction, then turned again and dove through the air toward the far side of the pond. When he landed tongues of water licked out and flashed in the gloaming.

I’d spent a lot of time among loons and had never seen this behavior before. Was she having fun? Was she exercising her wings? Was this his private ritual here on this pond so far from the hustle culture reducing us to filaments of ourselves? Did he learn this from his mother? Did she learn this from hers? Who was this loon that swam beside us all day without fear? All my life I had tried up until now to get close to one, but always they moved away as I moved toward them.

Not this one.

This one came within arm’s reach of Miss FPJ as they both bobbed around in what felt like a huge holy feminine embrace cradling us as we spun in circles around our star. Something tender and unmalicious and within us as much as around us. Something not separate from us, but us at our bests as well as our worst. Us when we are lonely. Us when we are tired. Us when we are sick. Us when we are aching for love or aching with love.

Us when we behold our beloved. Us when we part the soil and the roots and the filigreed mycelium to lay our beloved down. Us when we seize a fresh autumn apple in our fists. Us when we marvel at the huge heart of an elk still hot in our palms. Us when we cross the deserts of New Mexico 23,000 years ago and leave behind the spade shape of our feet in the crystallized sand. Us when our true friends say, I know.

That night a storm blew over and we had to scramble in the dark to shut the tent flaps. I was exhausted and curmudgeonly and I lost my cool for a second and made an ass of myself as well as a mental note to practice handling sleeplessness with more equanimity. We stayed dry, Dutch curled up at our feet like a wooly bear caterpillar, only he was a wet, stinky dog fouling up our nest. As romantic as camping is made to seem by purple prose, sleeping pads are poor substitutes for beds. I listened to the rain and hoped by morning it would move out. For a long time, I tried to get comfortable. The rain stopped. It was so quiet I could hear mosquitoes buzzing above the tent.

Then the loon caterwauled and every cell in my body jittered with recognition. This whole thing is indivisible. Noisy and cluttered as we’ve made it. Distracted as we abide in it. Plussed as we navigate it best we are able, it is but one immense miracle sweeping like virga through gravitational waves and electromagnetic fields. Through wars and accidents and unfurling grape leaves fated to demise at the insatiable appetites of invasive Japanese beetles.

Through divorces and through redemptions and through entombment in flowing lava. Through hemlock poisoning and through gun violence. Through riots and through stretches of time so long that original stories remain the same while all the characters change. The way it is in Arcadia when the different centuries merge onto the stage and the whole audience is made to see their individual lives as lineage and perpetuation of their ancestors and their ancestor’s ancestors and so on and so forth ad infinitum.

The loon spoke into the night air heavy with fallen clouds. I’ve always wanted to hold one. To hold something wild and free. To feel it beating in my hands the way a friend holds you as you let go of whatever haunts you. Say the way your father died on a motorcycle. Say the way the cancer won. Say the way your father took his own life on your birthday. Say the way alcohol killed yours. Say the way the old you died to make room for more love.

The loon spoke in its own language, phoning across time. It spoke in song of woods. It spoke in song of where we are going. It spoke in song of where we are when we notice.

It said, ego eimi.

I am.

Felt this one deeply.

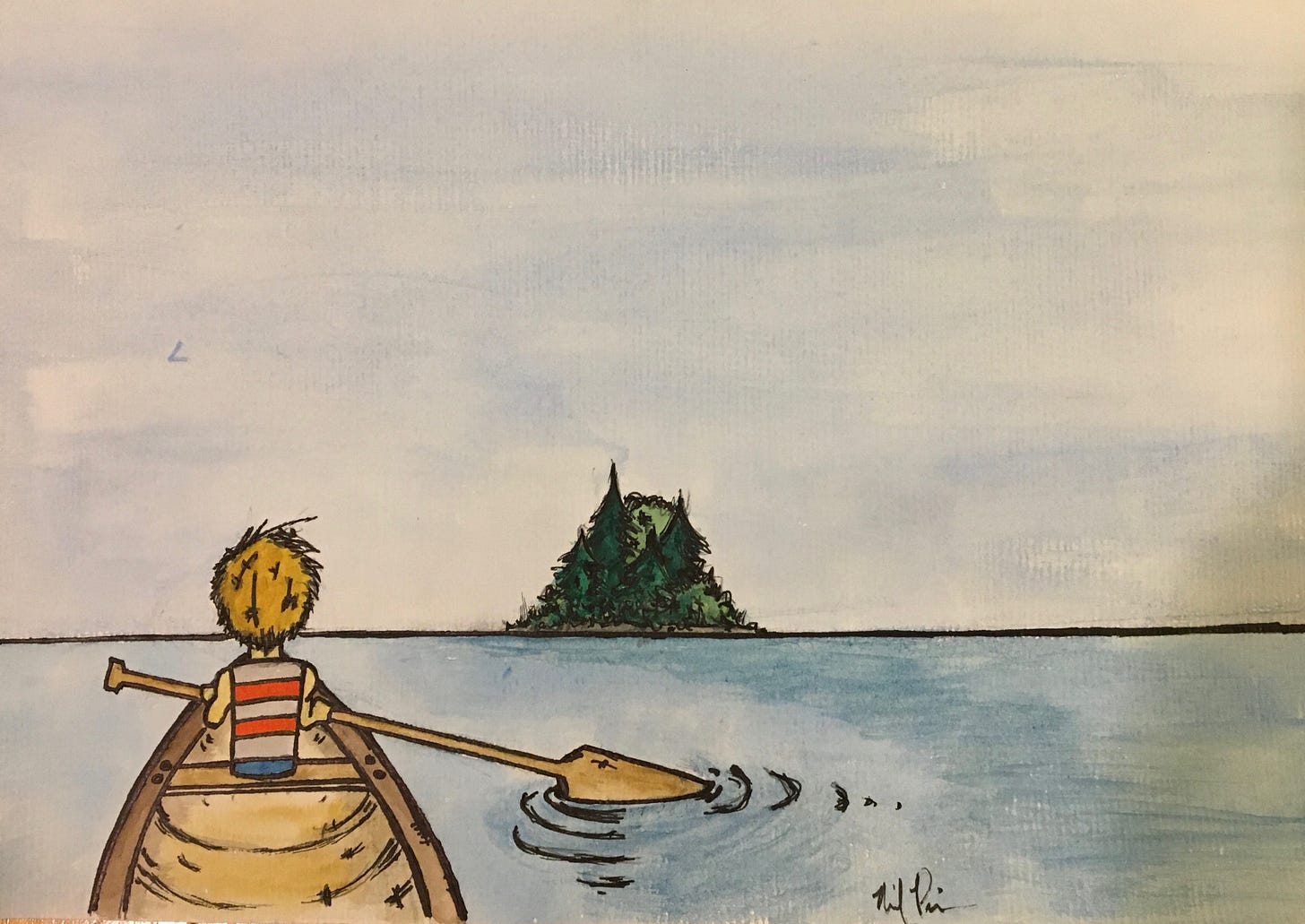

Us, one immense miracle. Well said. I had the good fortune to participate in a loon count on a lake in New Hampshire. For one hour I was to paddle the canoe in the assigned quadrant of the lake counting loons. (This is my kind of hour!)

The stillness was broken by a distant cry of a loon. About a hundred yards across the water a loon rose up and yodeled. Waited a moment and then resumed diving for fish. A more distant loon took flight up the lake towards the calling sound. We were a two loon day. This year only one pair has had two chicks, now one chick. Other years, there have been 4 or 6 pairs. There about a half dozen adolescent loons on the lake. By their behavior, I doubt loons learn much from their parents beyond back-riding. I doubt there is much meaning to be had in the actions of these rambunctious ruffians, other than an exuberance for life. We can relate.